The ideal gas law is one of the foundational concepts in thermodynamics. While it is based on a simplified model, it continues to serve as a powerful tool in many industrial applications.

What Defines an Ideal Gas?

An ideal gas is a theoretical model that assumes the following:

- Gas molecules are small, rigid spheres with no internal structure.

- The motion of the molecules is constant and random.

- All collisions between molecules are perfectly elastic.

- The average distance between molecules is significantly greater than the diameter of each molecule.

- Intermolecular forces are negligible outside of collisions.

This model becomes increasingly accurate at high temperatures and low pressures. However, it does not accommodate phase changes.

Derivation and Significance of the Ideal Gas Law

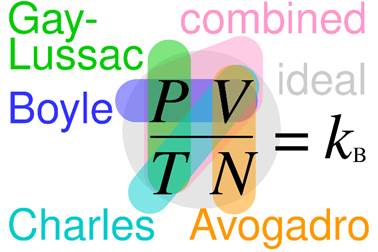

The ideal gas law is derived from three empirical gas laws:

- Boyle’s Law: Volume is inversely proportional to pressure (V ∝ 1/P)

- Charles’s Law: Volume is directly proportional to temperature (V ∝ T)

- Avogadro’s Law: Volume is proportional to the amount of substance (V ∝ n)

Combining these relationships yields the ideal gas law:

PV = nRT

Where:

- P represents pressure (Pa)

- V represents volume (m³)

- n is the amount of substance (mol)

- T is the absolute temperature (K)

- R is the universal gas constant (8.3145 J/mol·K)

This equation provides a fundamental relationship between the physical properties of gases and is widely used in engineering calculations.

Application in Industrial Gas Processes

In cryogenic air separation plants, the ideal gas law is applied primarily during the compression and purification stages. During compression, this law is essential for predicting changes in temperature and volume in response to pressure changes. It is also commonly used for unit conversion tasks. For example:

4,865 kg/h of gaseous oxygen (GOX) can be converted to Nm³/h of GOX, where the “normal” cubic meter (Nm³) refers to a gas volume measured at 0°C (273.15 K) and 1 atm absolute pressure:

These conversions are critical for process design, control system calibration, and equipment specification.

References

- Adkins, C. J. (1983). Equilibrium Thermodynamics (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Calvert, J. G. (1990). “Glossary of atmospheric chemistry terms.” Pure and Applied Chemistry, 62(11): 2167–2219.

- Çengel, Y. A., & Boles, M. A. (2001). Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Tuckerman, M. E. (2010). Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Molecular Simulation.

Leave a comment